With the Indian economy facing a dual challenge of slowing growth and rising prices, the first Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meet of 2025 comes burdened with expectations. Being the first MPC with the new Governor, Sanjay Malhotra, at the helm, it would also be taken as a signal of his monetary policy stance. As in the past, expectedly, the ‘growth-rate cut pitch’ will reach a crescendo in the run-up to the February MPC.

In the December 2024 MPC statement, former Governor Shaktikanta Das iterated that inflation concerns were a major factor for not cutting the policy rate. Given the inflationary pressures at that time, this was the right direction of monetary policy. Our questions are: have the inflation headwinds subsided enough to justify a rate-cut? Should MPC focus on growth instead of inflation now?

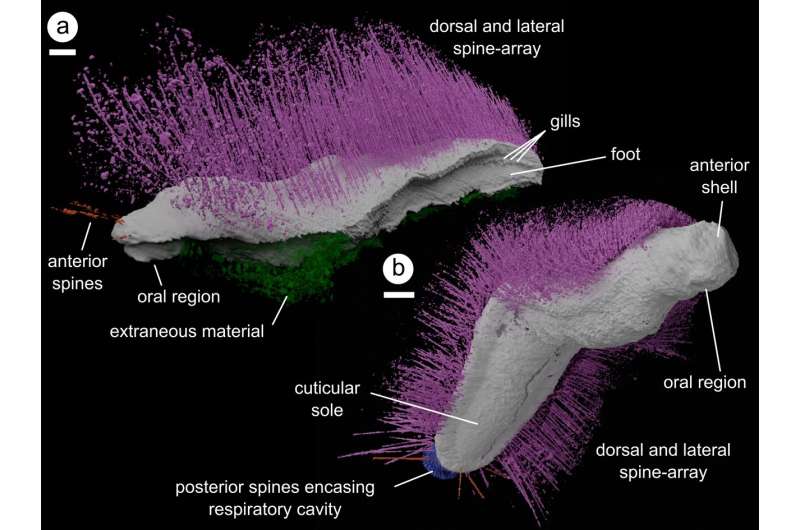

CPI Inflation: Positive signals: Chart 1 shows that CPI inflation for ‘General’, ‘Food and beverages’ and ‘Housing’ have moderated in the last two months. Post the ‘rate hike’ phase (shaded), CPI general and housing inflation have moderated. But food inflation has largely trended upwards, with a slight moderation in the last two months.

The housing inflation moderation is a positive development: but, given the challenges in data collection and compilation for this sector and the anecdotal experience of rising rentals throughout India, there is need to examine the movement closely.

Household inflation expectations: Moderation is less than expected. Using the Inflation Expectations Survey of Households (IESH) data from RBI, Chart 2 presents the data for three-month ahead expectations for general, food and housing price changes.

We present here the ‘Balance’: the difference between percentage of respondents expecting inflation to continue and the percentage of respondents who do not expect inflation. We can see that the household inflation expectations have moderated for general, but not for food and housing.

Food: the price to pay: The food prices trending upwards clearly show that food inflation has been stubborn. Food inflation will dominate household inflationary expectations as individuals, on a daily basis, are exposed more to food prices (than say housing or durables). Household inflationary expectations, in turn, are likely to influence consumption patterns and wage expectations.

For GDP growth to be ensured, consumption expenditure needs to be vibrant and wages stable, which means the central bank cannot ignore the movement of household inflationary expectations. Focussing on growth without taking care of inflation may not be a viable strategy for a populous emerging economy like India.

Thus, much as the policy rates cannot influence food inflation, the experiences of households regarding food inflation determine the trajectory of inflationary expectations in general and hence matter for the central bank. This strengthens the case for supply-side measures to tackle food inflation.

A holistic look at fiscal side policies for food inflation, keeping in view the procurement policies, exports of foodgrains and uncertain climate conditions is necessitated.

Will a removal of food from CPI basket help? A reduction in the proportion attributed to food in the CPI calculations may be required with the changing consumption basket, but a complete removal signals food does not matter for inflation experiences of individuals, a staggering assumption to make.

If the ultimate objective of monetary policy is the welfare of the people, removing food from the equation disconnects it from the reality. It seems hasty to reorient CPI, an indicator of prices for the economy as a whole, without the food component.

The policy rate dilemma

Undoubtedly the central bank has an unenvious decision-making ahead: with pressures from industry for rate cuts, banking sector facing a liquidity squeeze, and inflation giving a narrow breathing space.

Furthermore, the evolving geopolitical situation and consequent global capital movement frenzy has led to sharp depreciation and upward volatility of the rupee. The Federal Reserve has opted for a rate-cut pause: in this situation, any rate cut from the RBI will squeeze the interest rate differential, and put further pressure on the already abating FII flows.

The rupee situation, in fact, warrants that the policy rate not be cut at this stage. While exchange rate management may not be a monetary policy goal, the crashing rupee cannot be ignored at this point.

In the absence of an established empirical linkage between policy rate cuts and GDP growth, together with the evidence of negative impact of inflation on growth, the rhetoric on rate cut before every MPC seems misplaced. The inflation targeting framework of MPC has served us well till date, and ‘anchoring’ of inflationary expectations remains an important policy goal.

Trivedi is Associate Professor, National Institute of Bank Management; Das is ICICI Chair Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. Views are personal